By Courtney Morris/Virtual manipulative images courtesy of Nathanial Wiggins

When Dr. Nathanial Wiggins worked for a tutoring center, he used manipulatives to help students grasp concepts. Hands-on activities, he found, inspired critical thinking better than static images and text.

Years later, the San Jacinto College distinguished professor of engineering and mathematics has developed a mixed reality homework system technology to solve a similar need.

What he calls his critical thinking assessment technology not only helps teachers measure critical thinking but also gives students kinesthetic-style opportunities in the virtual learning environment.

How it began

Dr. Nathanial Wiggins

While artificial intelligence and augmented reality (AI and AR) were taking off in government and industry, Wiggins saw a disconnect in education.

Students often relied on one-dimensional images or text to understand complex concepts, even in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields. Meanwhile, teachers spent significant time grading short answers on tests, or they resorted to multiple-choice questions that didn’t gauge students’ understanding.

Instead, they needed 3D models and automatic assessment of free responses.

“Unfortunately, there are currently limited examples of these technologies in education,” Wiggins said.

Moreover, this technology often cannot integrate into learning management systems, which deliver course content, homework assignments, exams, and grades online.

Enter IMathAS. Created by a university researcher, this math interpreter system not only lets teachers program problem types but also interprets students’ free responses.

IMathAS offered a basis with libraries and other capabilities. With a server to store the system, Wiggins could develop his own system on top: “My specialization is designing a process to make things happen.”

What it looks like

Augmented reality technology for a math problem

Wiggins used HTML5 coding to design processes for his critical thinking assessment technology. Then he could deploy 3D virtual manipulatives, create neural networks to analyze short answers, and secure online testing.

He has implemented this technology in his own engineering classes and is helping colleagues and other institutions use these processes.

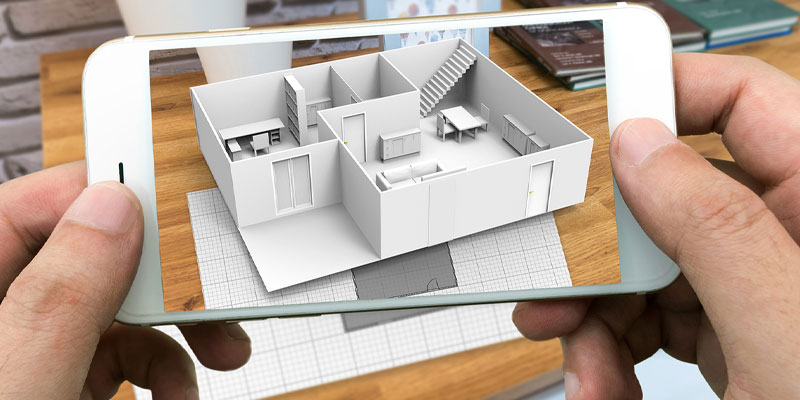

While many students don’t have access to virtual reality headsets, Wiggins realized they have the next best thing to view 3D manipulatives: smartphones.

Most new smartphones can run Google’s ARCore, software that allows the phone to interact with its physical environment. If students can’t deploy AR via their phones, they can see 3D images in their browsers instead.

“It really opens up that ability that we didn’t have before,” Wiggins said.

Beyond AR deployment, he also focused on neural networks — training a system to find data patterns and apply to future situations.

To package a test question, Wiggins gets three to five versions of the teacher’s desired response. He then matches student work to the teacher’s response at least 50 times so the system learns the desired response. Afterward, he creates a test set, aiming for 90 percent accuracy.

Since students can post answers to multiple-choice questions on cheating sites, automating assessment of free response not only saves the teacher time but also reduces cheating.

In summer 2020, Wiggins piloted his technology in two engineering classes with double blind studies. The result? Students who could deploy 3D models and get automatic feedback on their free responses scored much higher than classmates without these resources.

How it helps

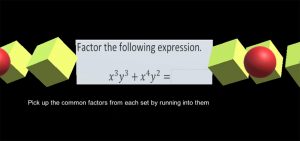

Mixed reality technology for an equation

From his tutoring days to present, Wiggins has seen most students excel with interactive learning.

“If you have someone with learning challenges and they’re trying to learn factoring, being able to turn that into something you can handle and move around … can make a huge difference,” he said.

Students also need instant feedback.

“They need successes quickly,” Wiggins said. “Early successes and quick feedback give them motivation.”

His homework technology provides both interactive content and constructive feedback.

Wiggins gives an example of students entering an online classroom: They click on a homework system with these built-in processes. They view a video-driven lesson with guided components, then get into the homework. Not understanding, they can deploy an AR illustration through their smartphones.

Next, they answer an open-ended question.The system gives feedback: “That’s on the right path. Elaborate.”

By the time students reach exams, they have mastered free response.

While ideal for STEM classes, the technology can work in any field, including liberal arts. For example, students could view historical event recreations and rotate 3D sculptures to view from all angles.

“I would like learning to be interactive, highly engaged so students can make quick advancement,” Wiggins said.

How others use it

The processes Wiggins has designed allow teachers to develop new problem types within the IMathAS system.

San Jac math professors Rebecca Heeth and Seann Sturgill use MyOpenMath, an IMathAS homework management system.

Heeth has programmed matrix questions that require students to show their intermediate steps. During 20-plus calculations, they can see where they went wrong and correct themselves instead of giving up. After Heeth implemented the system, her business calculus students scored 15 percent higher on their homework than students had from any previous semester. Their test scores rose too.

“Initially, I thought it might have [just] been that group of students, but the homework and test averages went up in every class I have implemented MyOpenMath since then,” she said. “I am using MyOpenMath in every course now.”

Sturgill also uses the free system in all his classes. Not only does it work on tablets and smartphones, but it also removes course material cost barriers since students are paying only for a scientific calculator, paper, and pencils.

“I find MyOpenMath more capable than other more expensive homework systems,” he said. “Students generally tend to do the homework more on this homework system than homework systems I have used in the past.”

What comes next

Wiggins sees applications for his technology processes in industry as well. San Jac already works with companies like Serl.io to further AR and mixed reality in business.

As he works out possibilities for his technology, one goal remains: giving instructors more ability to personalize their lessons and reach students in the virtual environment.

After all, his technology has made a difference in his own classes.

“Even though [students are] at home – isolated from the world – we can turn it into a rich learning experience,” Wiggins said. “Even in hard times, when some areas and some schools were seeing large drops in enrollment, San Jac’s engineering program didn’t see that.”